Peripheral Alacrity

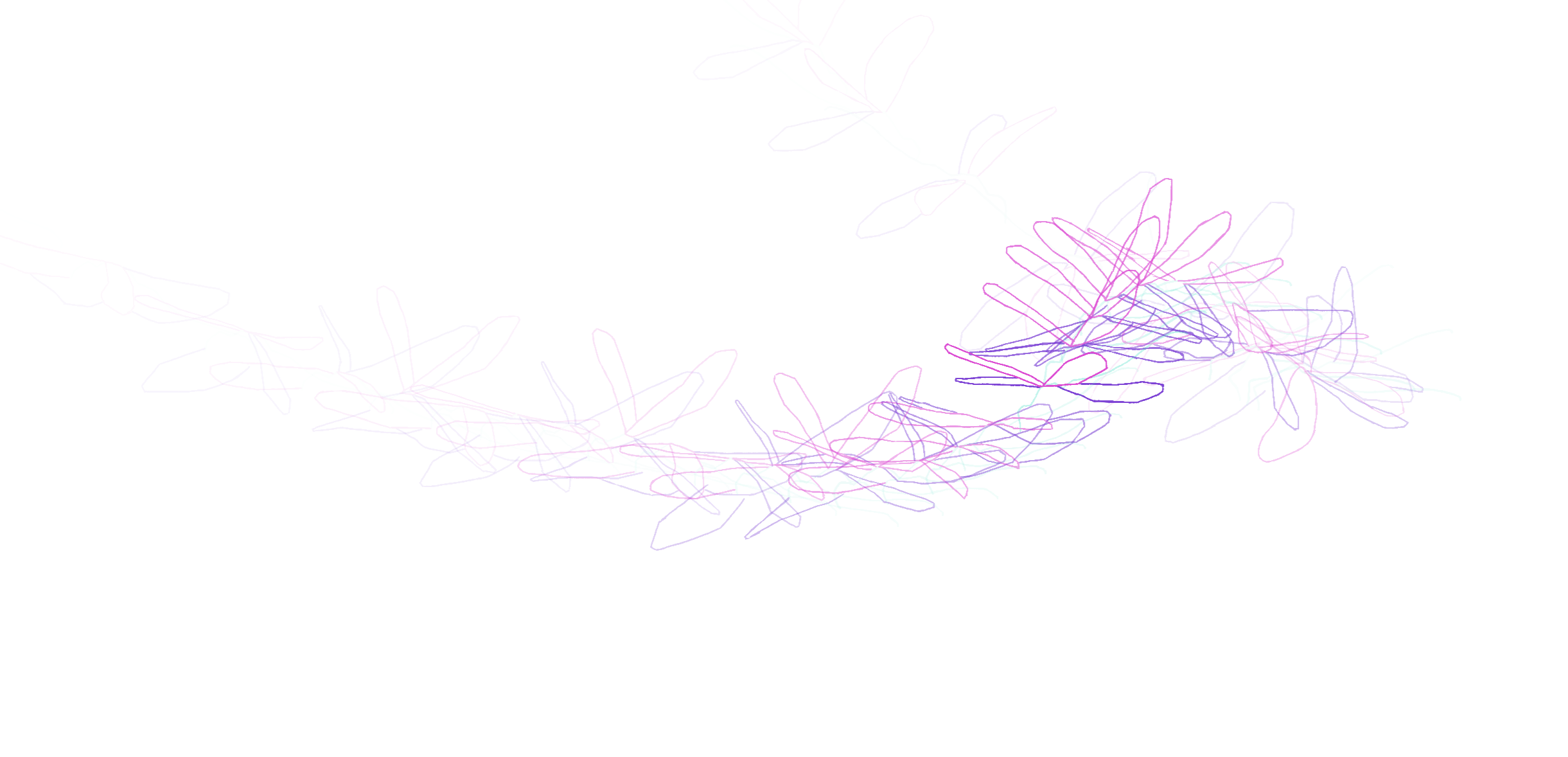

An audiovisual project utilizing animation at 60fps to investigate the temporal relationship between us and organisms on the edges of what we can see. The work seeks to capture a particular interaction characterized by fleeting peripheral glimpses of fast-living organisms; from dragonflies to some we only see as a passing blur, and all the abstractions in between. You’re interrupted by a flash of motion and sound from the corner of your eye. By the time you crane your head to look, it is already gone. It's less about seeing and more about our desire-to-see creating a dance between the viewer and the fleeting subject.

Creatures on the outer edges of our perceivable domain exist in this gray area between presence and absence. We typically interact with fast-living creatures in spontaneous vignettes. We are momentarily aware of a fly zipping by our ear, and reach out an arm to wave it away. They can hardly be considered proper social experiences, since we rarely process them quickly enough to react.

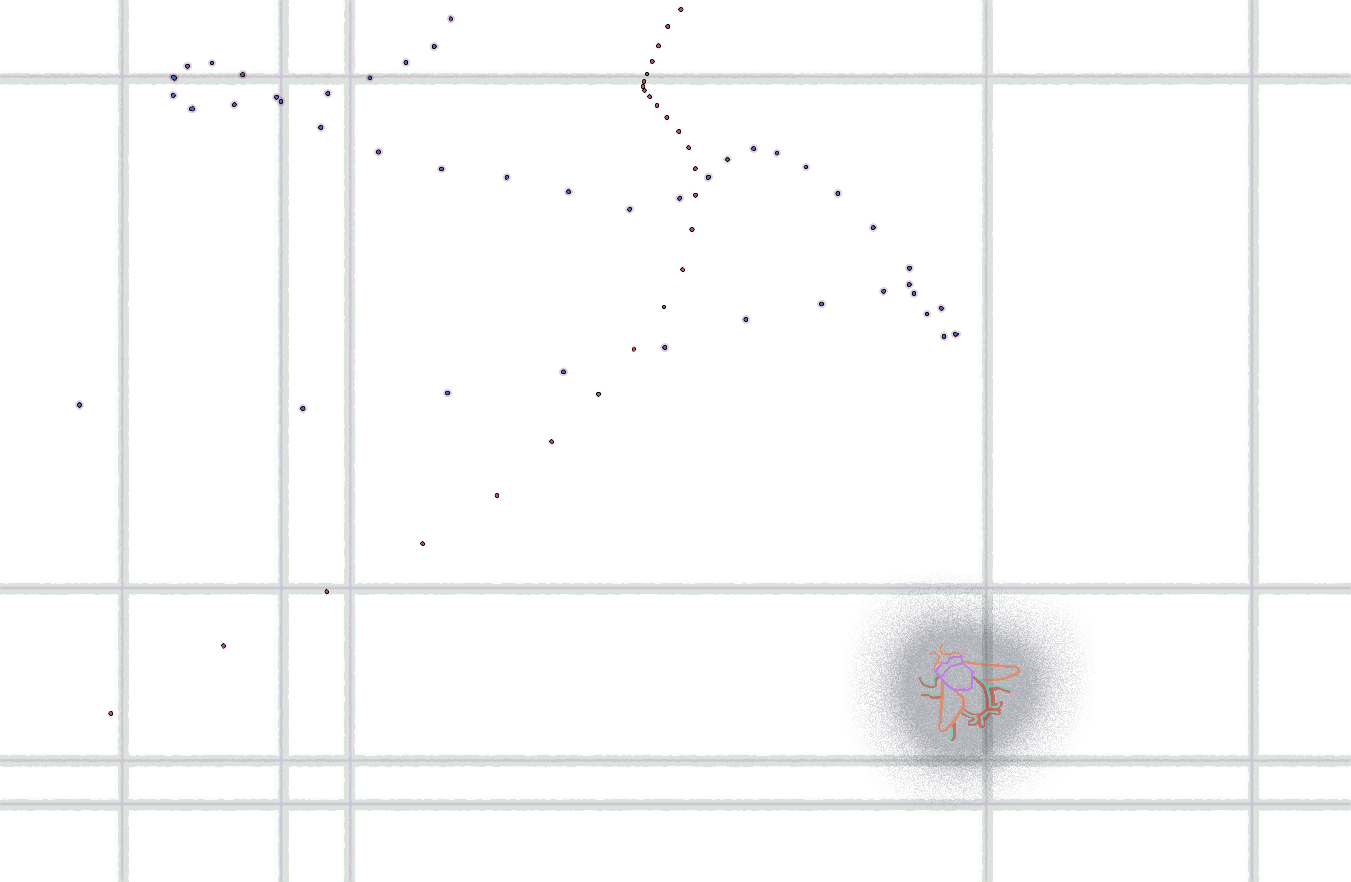

What is this sliver of time to an organism that perceives time slower than us? Scientists determine the ‘speed,’ or temporal resolution that different species are living by determining a creature’s Critical Flicker Frequency (CFF). A more well known name for this phenomenon is ‘persistence of vision;’ it is the point which flickering light stimuli becomes so fast the observer perceives it as a steady, continuous light. We know this as the visual phenomenon that grants the perception of motion to flickering images, making our world of film possible.

a human's CFF is 60Hz, a pigeon's is 100Hz, and a dragonfly's is 300Hz

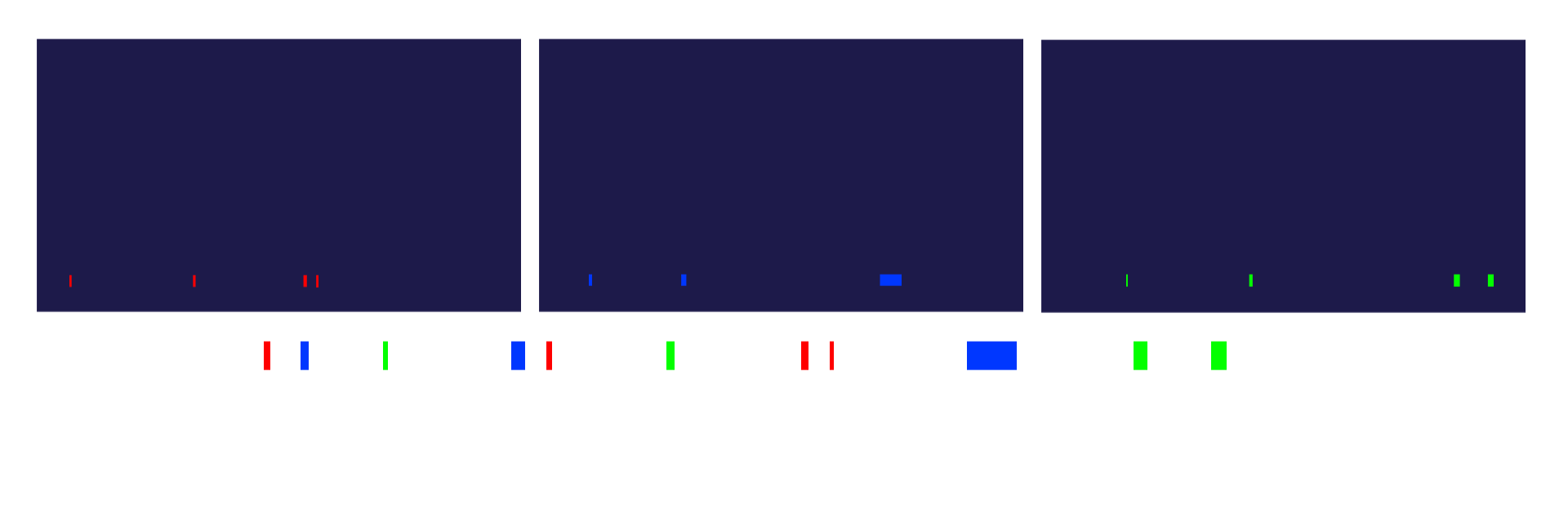

Framerate can be a mechanism for engaging with their temporal resolution. Doing 60 drawings/second (as opposed to the traditional 12 or 24) helps us to better explore the motion in milliseconds.

Using these terms as a starting point, we can begin to expose hidden dimensions to non-human animal temporality. For example, birds have an average CFF of 120Hz, a time-world twice as slow as ours. Slowing down a recording of birdsong to more closely match its temporal resolution reveals a level of nuance to its vocalization that we don’t normally catch.

Fast-living beings disrupt the predictable flow of our day-to-day life. We experience the dissonance between our desire to consciously observe/react and our temporal reality. Just barely, it slips through our grasp, denying us the satisfaction of clarity.

Part of working with fast-living critters is to reconcile with these emotions, which sometimes means loosening the perception of control over our own immediacy. The disruption of routine flows creates a point of departure in which new temporalities can be explored.

Genetic temporality is ancient, even present in bacteria, and takes form as biological rhythms. Every cell in the body has its own ‘clock(s);’ chemical oscillators that act as a kind-of feedback loop. The most famous of these is the circadian clock, which is entrained to the day-night cycle and commands us to go to sleep or wake up. We possess a vast overlapping collection of these ‘clocks,’ which determine a number of bodily rhythms from the timing of species migration to REM phases during sleep to the blinking of our eyes. This physical temporality attunes us to, and is attuned by, our surrounding world. It provides avenues for our bodies (particular in its design) to navigate our peculiar landscape.

We can find a mechanism, an axis of relatability, to ground ourselves in our interaction. An insect, many of which have a lifespan of one year, unable to bear the cold of winter they lay cold-resistant eggs in preparation for spring. They wont know the same kind comfort in the familiarity of passing seasons, and yet, summer must be an incredibly powerful notion if it is only experienced once. Perhaps we can think of the metamorphosis of their individual bodies as an extension of Earth’s metamorphosis, and vice versa. It is not just the reiteration of automatic cyclical processes, it is the manner in which insects are reinventing themselves at each solar revolution.

We can think of ourselves as a tree, or a tectonic plate; many generations of them will know our individual life. These are connections that move beyond the individual-individual domain and into more broad dynamics between collectives.

I’m seeking value in the brevity of the interaction and the asymmetry in temporal experience, creating momentum towards endless diversification. There are rhythms nested within rhythm, harmonizing with others. Sometimes all we can produce is a simple fleeting moment.

© Devon Pardue